Study probes utility of virus method for fecal detection

The Southern California Bight 2018 Regional Monitoring Program has completed a study that found that an alternative, virus-based method for tracking fecal contamination can be used as an effective complement for established Enterococcus bacteria-based methods.

The method comparison study, described in an article published in November by the journal Water Research, involved testing water quality at 12 Southern California beaches using a commonly used Enterococcus method alongside a newer alternative method that uses coliphage viruses to detect fecal contamination.

The study, conducted as part of Bight ’18 and led by SCCWRP, was motivated by recent efforts by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to develop regulatory thresholds for coliphage that will define for water-quality managers the levels at which coliphage contamination becomes indicative of a health threat to swimmers and others who enter recreational waters.

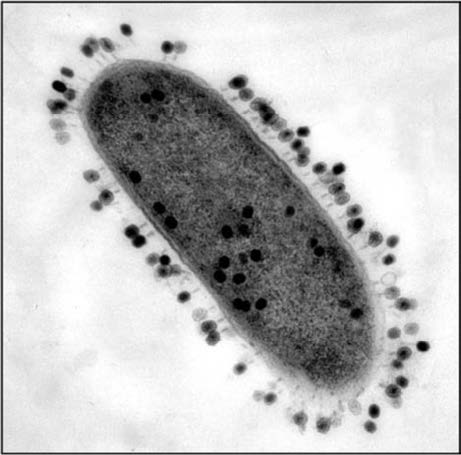

Coliphage, which is a virus that infects some fecal bacteria, more closely mimics the viral pathogens that sicken humans, underscoring the value of developing coliphage as a viral contamination indicator complementing Enterococcus and other bacteria indicators.

Human health thresholds for Enterococcus-based monitoring have been in place for more than two decades. In 2018, the EPA released an approved coliphage-based method for quantifying fecal contamination at beaches and other recreational water bodies.

In advance of the EPA’s possible release of coliphage thresholds, the Bight ’18 monitoring program tested the new coliphage method’s utility side by side with a decades-old Enterococcus testing method. The study’s goal was to evaluate the efficacy of routine monitoring of Southern California beaches using coliphage as an indicator for the presence of fecal contamination.

The Bight ’18 beach water-quality study showed that coliphage-based monitoring is more likely to protect the health of beachgoers in certain scenarios, including where a fresh sewage source is present, such as beaches in southern San Diego County where lightly treated sewage can travel north from Mexico and contaminate coastal waters. In this scenario, the data from coliphage-based monitoring are more likely to support beach-closure decisions and postings of advisory signs.

At the same time, the study found that if public health decisions were to be made based on the coliphage data instead of the Enterococcus data, fewer beaches would be closed and fewer beachgoers would be warned about potentially polluted waters – meaning that using coliphage testing method would, on average, be less likely to protect beachgoers from exposure to contaminated waters.

The study also found that both methods generally perform reliably for detecting fecal contamination at beaches, although the coliphage method is comparatively more difficult to perform and requires larger water sample volumes.

The Bight ’18 study involved measuring fecal contamination at 12 beaches across Southern California measured during both wet and dry weather. The coliphage and Enterococcus methods produced statistically similar results at 73% of study sites.

No U.S. regulatory agency has indicated that coliphage-based fecal contamination testing will become a requirement for routine beach water-quality testing. The results of the Bight ‘18 study suggest that the coliphage method is a valuable supplement to – but not an appropriate replacement for – Enterococcus testing at Southern California beaches.

Prior to 2018, an EPA-approved coliphage method for detecting fecal contamination did not exist for beaches and other recreational waters, although a coliphage method for testing groundwater has been available since 2001.

For more information, contact Dr. Joshua Steele.

More news related to: Microbial Risk Assessment, Microbial Water Quality, Regional Monitoring, Southern California Bight Regional Monitoring Program, Top News