Study shows acidification triggering adverse biological impacts in Dungeness crab larvae

A three-year study examining the sensitivity of Dungeness crab larvae to ocean acidification along the U.S. West Coast has found that this commercially important species already is being adversely impacted by intensifying ocean acidification – a finding that has reshaped scientists’ understanding of the intensity and speed at which low pH waters can impact coastal biological resources.

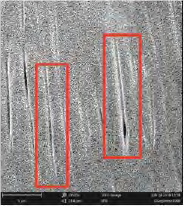

The study, published in February by the journal Science of the Total Environment, documented dissolution of the exoskeleton, or carapace, and mechanical sensory organ loss in the larvae of Dungeness crab in the Pacific Northwest marine environment.

Previously, scientists thought that Dungeness crab were comparatively much less sensitive to acidification than other marine calcifiers, and that impacts of this magnitude would not manifest for decades.

The study, which was led by SCCWRP in cooperation with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, emphasizes that much more research is needed to understand the long-term implications of this stress on crab growth and development.

For example, if crab larvae are diverting more energy to repair their exoskeletons, the portion that develop into adulthood may be decreasing over time – a trend that could fundamentally alter harvest yields and timelines for a $270 million U.S. West Coast industry.

During the study, researchers analyzed crab larvae samples collected during a 2016 NOAA research cruise along the U.S. West Coast. The study documented severe dissolution in the exoskeleton that is leading to slower growth.

Researchers also for the first time found that the changing ocean chemistry is causing damage to receptors on the shell that transmit important chemical and mechanical sensations, including potentially helping the crab navigate its environment. The canals from which these mechanoreceptors extend are being damaged by acidification and, in some cases, the receptor is falling out entirely.

Dungeness crab depend on a seawater mineral known as calcite – a less soluble form of calcium carbonate – to build their exoskeleton. Researchers previously believed the organism’s reliance on calcite would make it less vulnerable than organisms like pteropods that rely on calcium carbonate. Calcium carbonate is becoming increasingly less available as a result of coastal acidification.

The study’s findings underscore the potential to use crabs as a management tool for tracking the intensifying biological impacts of West Coast acidification. SCCWRP in February convened a panel of leading global experts on decapods to develop consensus on biologically relevant thresholds at which these marine organisms can be expected to experience adverse impacts from acidification.

These tools, combined with field monitoring data, will help researchers develop methods to delineate hotspots for Dungeness crab sensitivity and design routine monitoring programs for tracking biological impacts, especially in combination with other stressors.

Already, SCCWRP has begun working with the University of Southern California to design laboratory experiments examining how acidification in combination with other climate changes stressors like low dissolved oxygen levels can impact physiological development for Dungeness crab larvae.

For more information, contact Dr. Nina Bednarsek.

More news related to: Climate Change, Ocean Acidification and Hypoxia, Top News